Institutions getting serious about ESG have been harnessing new data partnerships and artificial intelligence. Amid all the hype, can firms show the substance behind their statements?

The megatrend of aligning investments with environmental, social and governance factors (ESG) is reaching greater levels of sophistication, with new metrics that can evidence a company’s seriousness about such issues.

Several participants are taking up new approaches to demonstrate their sustainability credentials: using artificial intelligence, academic research and data partnerships to determine how advantageous their portfolios can be against these criteria.

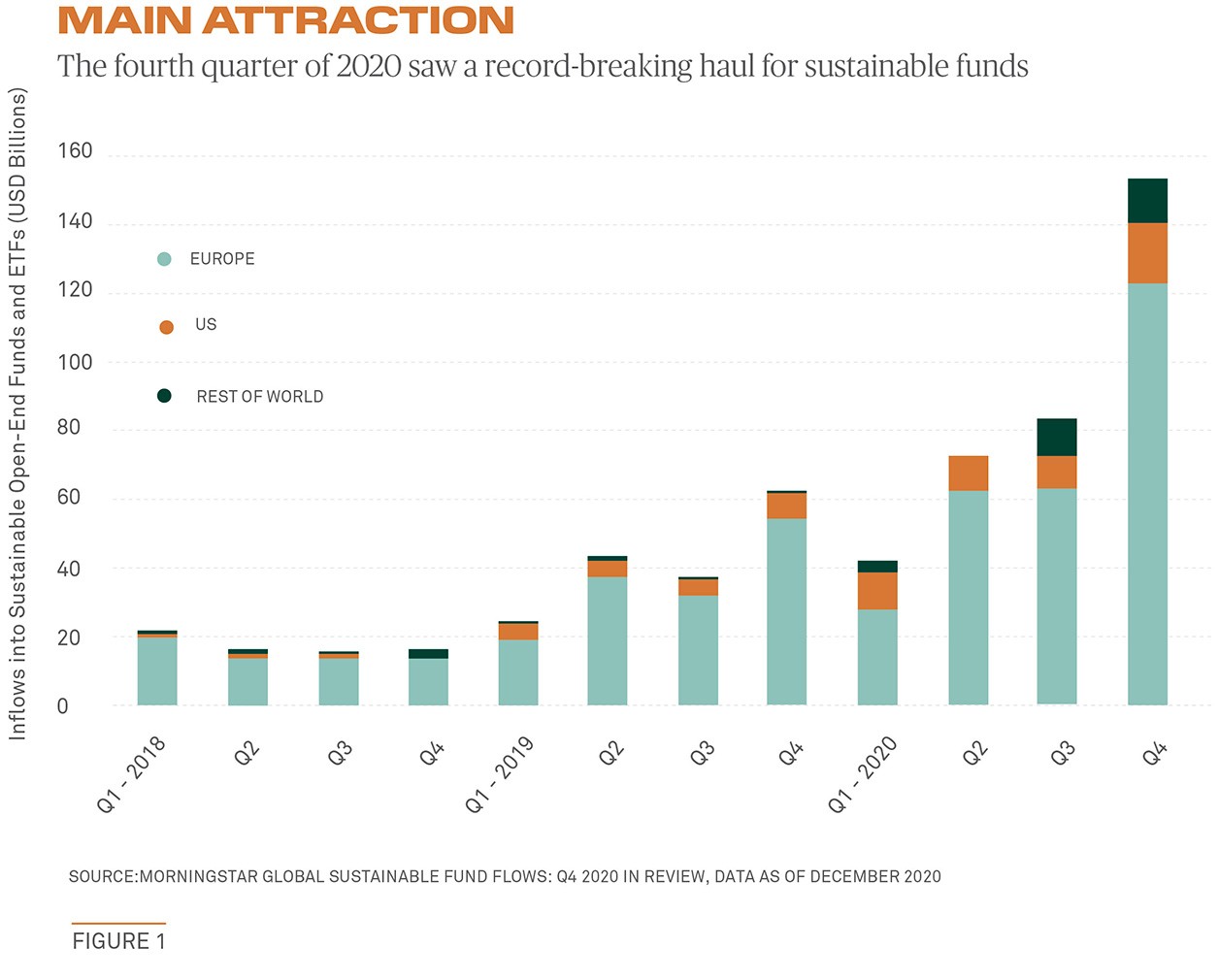

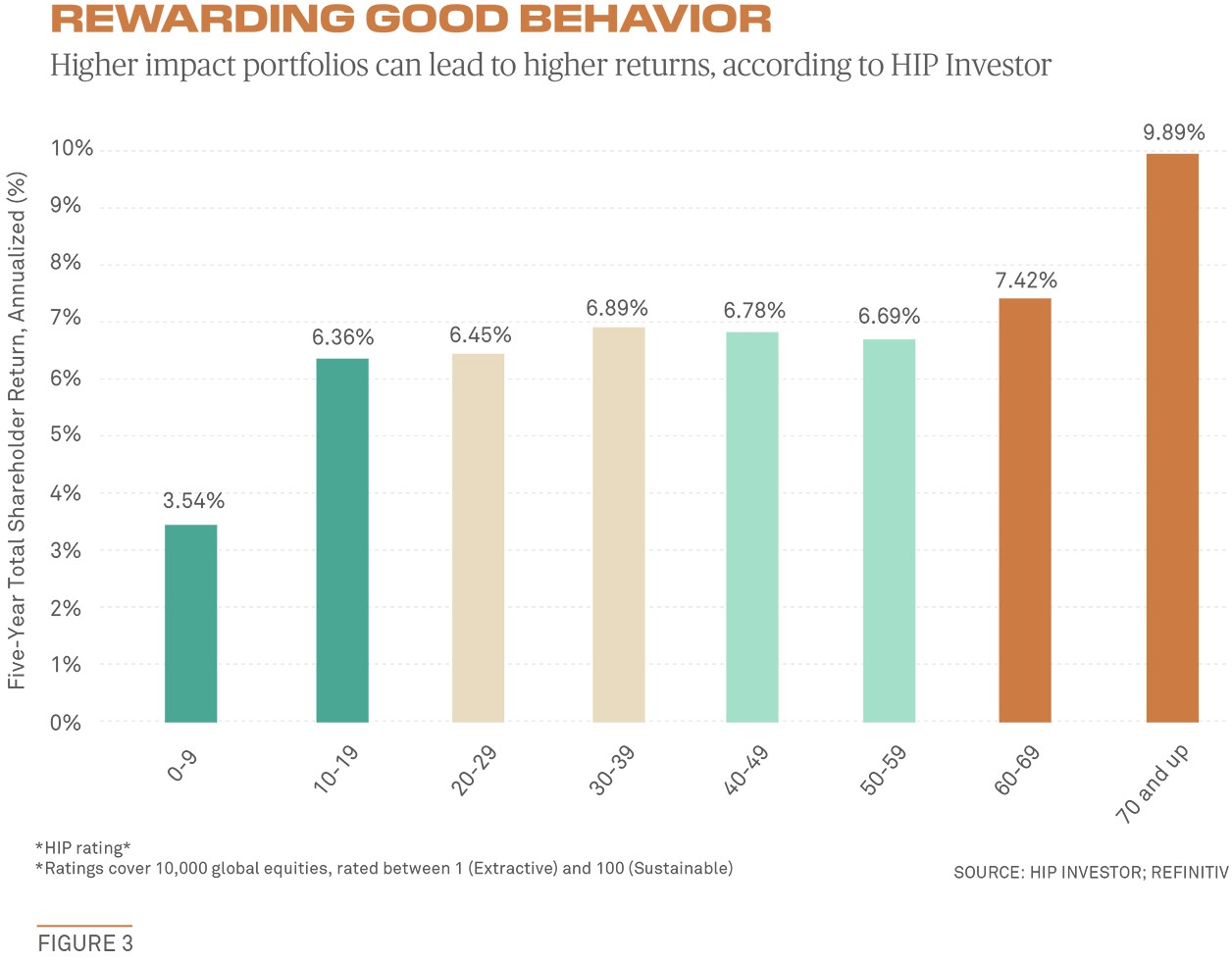

The push comes at a critical juncture. Even in the midst of a global pandemic, ESG investing saw a record-breaking quarter in the final stages of 2020. Global inflows into sustainable funds were up 88% in the fourth quarter, and a record 196 sustainable fund products launched in the period, according to researcher Morningstar (see figure 1).

U.S. mutual funds claiming to be dedicated to sustainable investing also outperformed their traditional peer funds; by 4.3 percentage points on a median total return basis in the case of equity funds and 0.9 points for bond funds, Morgan Stanley found.

At the same time, pressure is mounting for investors and issuers to prove they are not making false claims about how sustainable their businesses or products are. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission in March said it was contemplating a new disclosure framework and promising that its Climate and ESG Task Force will “identify ESG-related misconduct.” The European Commission in 2018 announced a new action plan that will mandate how the market defines sustainability and reports on sustainable investments.

Theodor Cojoianu, assistant professor in finance at Queen’s University Belfast and member of the EU Commission Platform on Sustainable Finance, says companies and investors will be forced to improve their disclosures. “This is not a voluntary, feel-good initiative — this is legislation under which the lack of robust compliance can result in legal consequences,” he says. “It’s a game changer, and data is at the center of it.”

Tailor-Made Technology

Investors are becoming much more specific in communicating the data they use — whether it’s for portfolio management, managing risk or trying to create impact. That is creating a role for cutting-edge technology, including artificial intelligence (AI).

Singapore-headquartered technology company BlueFireAI curates reams of data using artificial intelligence to help banks and asset managers get early warnings of bad apples among their investments. Clients connect with an avatar called Emmalyn on industry chat platform Symphony, and she provides a forward-looking risk assessment — red, orange, yellow — on different listed companies. “Our clients are renting her brain,” says Luke Waddington, co-founder and CEO.

Salt Lake City-based technology company Causality Link has developed a natural-language processing platform that extracts hundreds of categories of information related to ESG, tagged against listed companies. These signals aggregate the perception of more than 8,000 news publishers worldwide to track the percentage of favorable coverage in real time, says Eric Jensen, the company’s founder.

Banks have customized technology, too. Citigroup has a dashboard that allows investors to set their target ESG preferences, compare their portfolio of securities to those rules and identify companies that need further assessment. BNY Mellon has an analytics application that allows investors to input their sustainability preferences, select the most appropriate framework and data to communicate them, and assess or construct portfolios accordingly. For example, if a client wanted to invest in cleaner cities, that firm could choose the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals framework and see how well investments are performing on issues like reducing air pollution and building city parks.

Rather than being limited to specific data providers, the app’s infrastructure allows for all data sources to be captured. The app crowdsources anonymized and aggregated information on the investment themes and data preferences of investors to guide both asset owners and asset managers.

“This is legislation under which the lack of robust compliance can result in legal consequences. It’s a game changer, and data is at the center of it.”

THEODOR COJOIANU, EU COMMISSION PLATFORM ON SUSTAINABLE FINANCE

“We anticipate an avalanche of data as it becomes more granular and as new types of information emerge as critical, so the application has to be scalable,” says Corinne Neale, global head of business applications at BNY Mellon.

Technological solutions also are promising to catapult the market for green bonds. One sustainability bond issuer looking to technological solutions is Dallas-based On The Road Lending, which provides reasonably priced loans to low-income Texans to enable them to purchase safe and energy-efficient cars.

A planned sustainability bond from the nonprofit will help pilot a new BNY Mellon service called Quantum GreenSM designed to help companies demonstrate that the use of proceeds from their issuance will meet certain criteria they have selected.

On the digital platform, issuers will be able to decide what framework or standard they want to use to structure their green bonds, and ultimately have third-party ESG service providers help verify that their deals align with those guidelines.

For green bonds, issuers have traditionally used the International Capital Market Association (ICMA)’s Green Bond Principles since their launch in 2014. The EU’s Green Bond Standard (EU GBS) could also be an option for issuers and investors in the future.

A structured and guided approach like the one from BNY Mellon can help issuers through the pre-issuance stage and potentially also streamline and optimize post-issuance obligations, such as “Use of Proceeds” and “Impact” reporting, according to Michelle Corson, On the Road’s founder and CEO.

Quantum Green “will help the issuer to ensure that they’re reporting fairly and accurately and gives much more confidence to the investor,” she says.

Doing It For Themselves

Metrics form the backbone of sustainable finance — from underpinning passive indexes to calculating how much a portfolio will be financially impacted by climate change. The issue is the overlapping disclosure frameworks, which are reported against inconsistently, only to be passed to data vendors that have wildly differing ESG ratings for the same companies.

In this context, many investors have decided to take ESG scoring into their own hands. Andrew Parry, head of sustainable investment at BNY Mellon’s Newton Investment Management, overseeing £46 billion ($64 billion), says much of the investment industry is seeing a move away from using exclusively third-party ESG ratings, toward building customized sustainability scores from a patchwork of external data and ratings. For its own stock picking, Newton analysts use raw data to assign separate E, S and G scores; an aggregate score; and a score indicating how Newton expects the company to rank in three to five years’ time.

“The problem with a rating is that it’s a summary of a lot of complex, nuanced inputs that change over time,” Parry says. “Investors are now often choosing to internalize that process — to do their own research and rely on their own interpretation of what ‘good’ looks like.”

The Florida State Board of Administration, which manages $250 billion, mostly on behalf of public retirement funds, has started developing internal ESG ratings to help it link sustainability factors to returns, earnings and financial ratios. Mike McCauley, its senior officer of investment programs and governance, says the metrics — likely to take the form of company-level scores — will be based on external ESG ratings that will guide the board’s engagement as a shareholder with companies to where it will have the biggest impact on returns.

UK- based investment firm Insight Investment, overseeing $976.4 billion, also as part of BNY Mellon, has built its own proprietary ESG ratings system by taking data inputs from multiple providers and weighting each factor by importance. It cites German digital payment company Wirecard, which filed for insolvency after a string of fraud allegations last year, as a case in point. It did not invest in part because the company received the worst possible ESG risk rating in Insight’s proprietary model, while other data providers didn’t make such a damning assessment.

Quantum GreenSM “will help the issuer to ensure that they’re reporting fairly and accurately and gives much more confidence to the investor.”

— MICHELLE CORSON, ON THE ROAD LENDING

Third-Party Ratings

ESG ratings providers like MSCI and Sustainalytics, which was acquired by Morningstar last year, are adapting to these shifts, with many having made their ratings freely accessible.

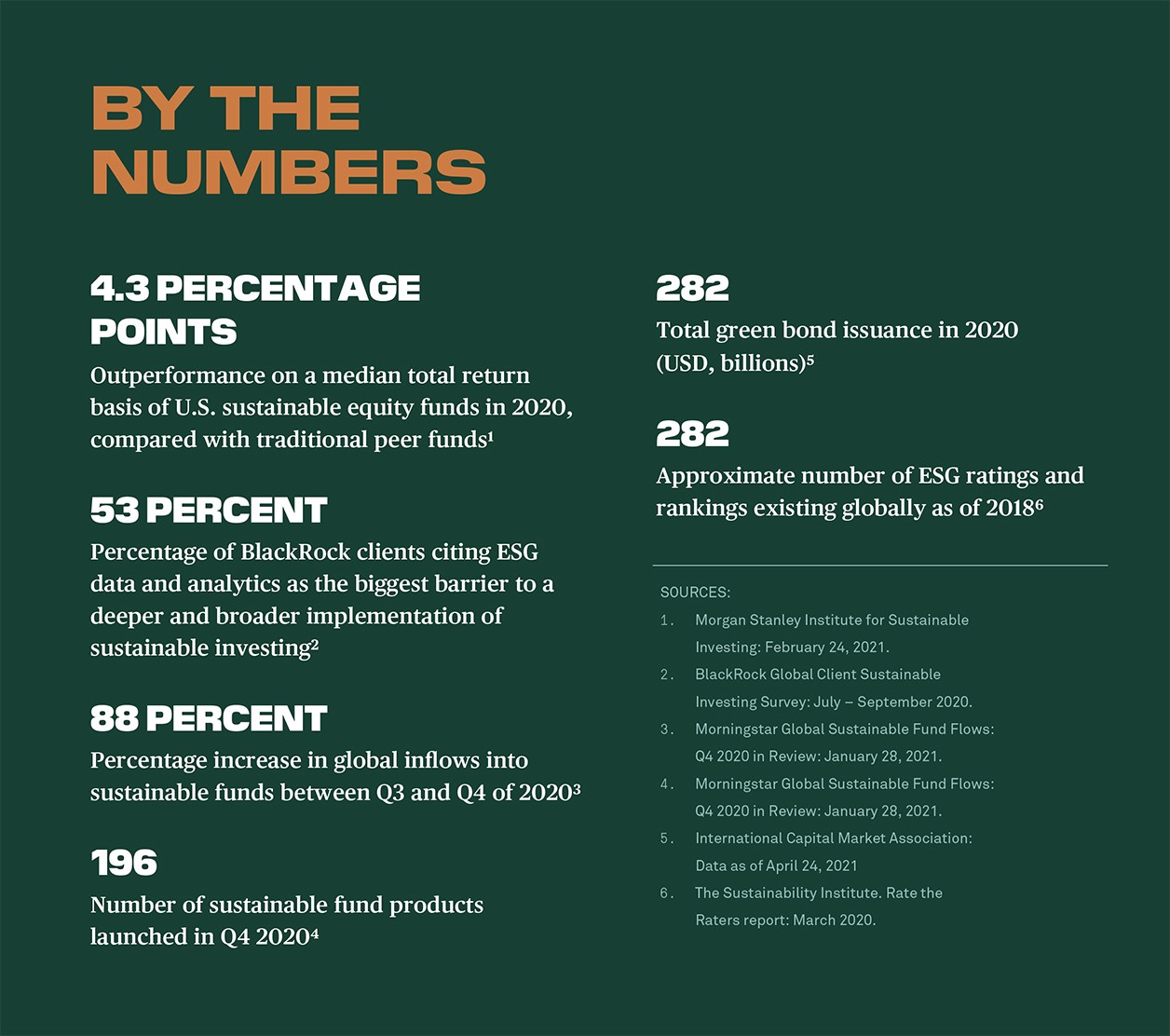

Bob Mann, president of Sustainalytics, says inconsistency in ESG ratings isn’t always a problem. “For active managers who are trying to unlock proprietary insights, they don’t have the same desire for consistency,” Mann says. “In fact, it would devalue that rating if all the ratings had the same result.” The firm now creates separate products supported by two separate research teams and datasets. Its flagship ESG rating is based on risk (see figure 2), and it also has new company-level impact metrics.

Traditional credit rating firms Moody’s Investors Service and S&P Global Ratings, having both acquired specialist ESG ratings firms in 2019, are now offering sustainability scores for companies, in addition to their bread-and-butter credit ratings. Beth Burks, S&P’s director of sustainable finance, says the firm’s 60 ESG evaluations so far were derived from an entity’s past ESG performance, as well as its preparedness for disruptive factors such as technological advances and geopolitical swings.

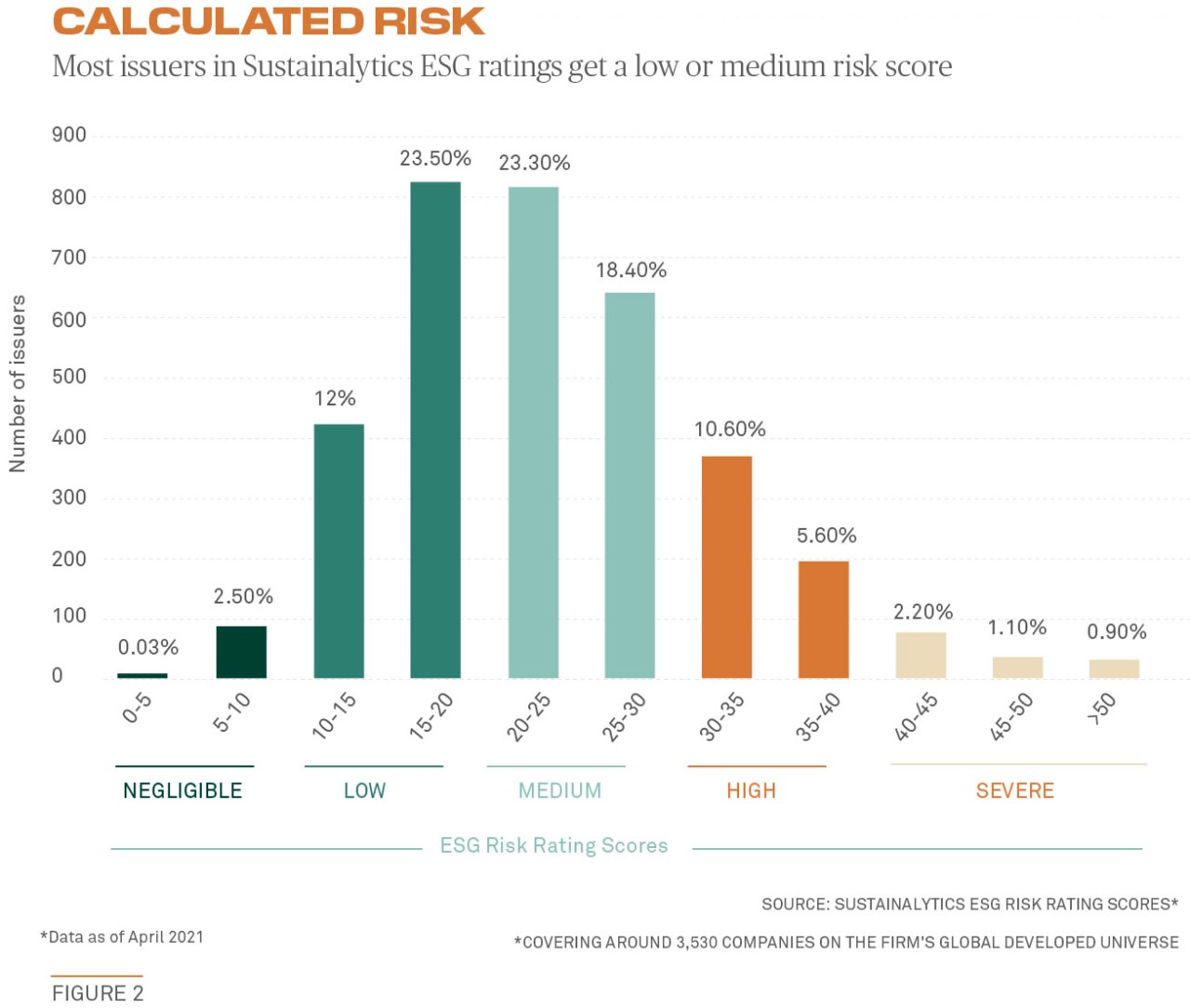

Data can also help investors compare the credentials of different securities. San Francisco-based HIP Investor has developed a proprietary ESG rating system that can be used to rank not just 130,000 issuers, but one bond or stock against another.

The HIP system analyses and condenses eight million data points over five pillars — health, wealth, earth, equality and trust — to produce an overall ESG score between 1 (extractive) and 100 (sustainable). Paul Herman, co-founder and CEO of HIP, says a high HIP rating generally can be linked to lower financial risk and higher returns (see figure 3).

BNY Mellon’s bond desk is working on incorporating rating scores into its inventory runs so traders can check the rating before making a decision whether to buy or sell. Data can also help investors compare the credentials of different sustainability-related bond issuance at a time when issuance has risen exponentially since the world’s first green bond was launched by the European Investment Bank (EIB) in 2007.

Charles Goodwin, BNY Mellon’s head of public finance and co-head of social investing, makes the point that different bonds from the same issuer could have different ESG scores. For example, a technology multinational should have one ESG score if issuing a bond for their general corporate purposes, but a totally different score if raising money for solar panels.

Partnerships With Academia

Other investors have turned to academics. The Yale Initiative on Sustainable Finance has a new workstream aiming to establish where sustainability pays off financially. Heading up the project is professor of environmental law and policy Dan Esty, a former U.S. Environmental Protection Agency official and negotiator for the 1992 Framework Convention on Climate Change and NAFTA.

According to Esty, ESG metrics in their current state are missing a key element — a correlation to materiality; in other words, whether a certain ESG factor affects the financial performance of a company. To rectify that, Yale will utilize large extracts of anonymized and aggregated custody insights from BNY Mellon and try to indicate which existing ESG factors are “usefully” tracking sustainability, and which funds are really delivering financial performance and sustainability.

The hypothesis is that some sustainability factors will be associated with financial outperformance while others could cost money to implement and therefore cause the company to lag in terms of financial performance, Esty says. A company offering more time off to employees, for example, might not match the results of its peers.

In Taiwan, Cathay Financial Holdings — the country’s largest financial group, with $390 billion in assets — has been working with academic institutions to fill domestic ESG data gaps. In one instance, that is by collaborating with Taipei University’s ESG research on 300 Taiwanese companies and a survey on responsible investment.

Cathay’s CIO Sophia Cheng says it’s crucial for Taiwanese companies to report on ESG so as not to lose out on foreign investment. “Taiwan depends on exports, so if corporates don’t understand ESG and global supply chain requirements, they’ll lose business opportunities and institutional investors as shareholders,” she says.

Taiwan is fast becoming recognized as a hub for sustainable investing, with around 15% of new fund launches in 2020 having an explicit ESG focus, according to Fitch Ratings.

Meanwhile, asset managers and owners have been working with sustainable finance researchers at University College Dublin and Queen’s University Belfast to explore expanding the coverage of a machine-learning tool that aims to help investors identify “greenwashing.”

The tool being tested, named GreenWatch, compares 700 companies’ claims about their sustainability with data about their carbon performance in their annual reports to assess whether they are accurately representing their green credentials. Now the team wants to scale the tool to cover more companies across further indicators, including climate change adaptation, biodiversity and water.

Toward A Sustainable Economy

With one in four of all European ETFs launched last year having a climate focus, according to Morningstar, it’s clear that climate change is fast becoming the biggest issue on many investors’ sustainability agendas.

Partly off the back of the 2017 recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, founded by the Financial Stability Board and chaired by Michael Bloomberg, investors are ramping up their analysis to try to quantify how much their portfolios will be impacted by climate change.

Investors including Axa, Aviva and Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund have started to adopt metrics to determine the so-called climate “warming potential” of their activities. For example, Axa has worked with Zurich-based fintech Carbon Delta — now part of MSCI — using the “warming potential” metric as a key climate indicator.

Investors are also looking to express their personalized ESG approaches through their securities lending programs. The Risk Management Association, for example, maintains that securities lending can “align with — and even enable — positive ESG outcomes.” The International Securities Lending Association (ISLA) formed an ESG Steering Committee last year, which includes a beneficial owner-led focus group, developing a best practice framework and most recently making five pledges around ESG. The Pan Asia Securities Lending Association (PASLA) is also working with the industry to create the continent’s own set of ESG principles.

Ina Budh-Raja, BNY Mellon’s EMEA head of product and strategy in securities finance, says clients are looking for confidence that they can exercise their long-term stewardship objectives at the same time as lending their securities. They want to express their ESG strategies through their portfolio construction and engagement with investee companies, and also apply their ESG acceptability parameters through to their collateral holdings.

BNY Mellon is exploring the use of data analytics solutions to help asset owners lend their securities with ESG parameters, both in relation to stocks and bonds received as collateral and reinvestment of cash collateral. Budh-Raja says this could involve using a multi-vendor approach to better inform clients seeking to evaluate their collateral against ESG standards and regulatory taxonomies.

Some say it will be important for taxonomies to account for stocks that are in a transition phase, as well as those that are currently deemed to be sustainable. There are broader concerns in the market that carving out large chunks of stocks from collateral pools — as opposed to allowing for stocks that might be improving their sustainability — could have undesirable consequences for market liquidity.

Even so, while investors are undoubtedly becoming more sophisticated on ESG as they combine datasets and refine their sustainability data requirements, key challenges remain in meeting regulation requirements. The EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation, which has just recently taken effect, imposes heightened reporting requirements across all asset classes to address greenwashing and impact-washing at the asset manager and asset owner level.

But data gaps mean compliance with these can be a challenge, according to Arthur Carabia, director in market practice and regulatory policy at ICMA. For example, issuers of green bonds often report on the reduction in carbon emissions provided by a project rather than the total emissions of the project itself. Another avenue for investigation is “geospatial” data mapping assets to climate and biodiversity risks and impacts — touted by the Future of Sustainable Data Alliance but yet to be harnessed meaningfully at scale.

Investors are still coming up against ESG data obstacles, with 53% of BlackRock clients citing data and analytics as the biggest barrier to a deeper and broader implementation of sustainable investing, according to a recent survey.

Either way, a step change is clear in sustainable and climate finance regulations. The London School of Economics has found that central bank and supervisory action on climate change and sustainability is fast becoming the new normal, signaling that sustainable investing is here to stay.

Sean Kidney, CEO of the Climate Bonds Initiative, says the sustainable finance policies, particularly in the E.U., mark a turning point for data.

“It’ll be painful in the short term, but ultimately we’re going to get the deeper data on assets that we need as companies are forced to put data out there. There’s going to be a revolution in the next two years.”

“This is legislation under which the lack of robust compliance can result in legal consequences. It’s a game changer, and data is at the center of it.”

THEODOR COJOIANU, EU COMMISSION PLATFORM ON SUSTAINABLE FINANCE